I am squeamish, which is a fact that took me almost three full decades to finally admit — though the fact that I can’t even look at photos of sponges, pancake batter, or coral reefs should have been my first sign (shoutout fellow trypophobics — not even looking up if that’s spelled wrong for fear of the images it’ll furnish). Seeing or thinking of viscera, veins, tissues, and bones sends me into a tailspin, which is why I happily sat out Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, and especially The Pitt.

Since Hollywood has taken a stance on bodies (no to them having sex, yes to them exploding and bleeding out of their eyeballs), every trailer now features Red Asphalt-level gore. I’m dealing with it, but I was personally aggrieved by the presence of a fucking spinal cord dangling from a decapitated head above the Tatsu-ya Ramen on Melrose.

Much of the discourse around 28 Years Later has focused on a supersized sex organ, but I was most struck by the fact that by the time a character is baking and rinsing pink brain matter off a skull, I’d already come out from behind my fingers. It was as if something had transformed — a body is a body, after all. Once the soul is gone, what’s left to fear?

In the first act of the movie, Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) takes his son (Alfie Williams) a-huntin’ for the Infected, people who have been zombified by a primate-borne “rage virus” for 28 years. When they encounter a man who’s been strung up like a tetherball for the horde of infected zombies to attack, Jamie urges Spike, to kill “it.” When the boy hesitates, Jamie reminds him that the virus has taken the man’s soul — what made that person’s life valuable is no longer in the building. It’s not a subtle metaphor in any regard: much of the first part of the movie is set up to echo how we view each other in war time — us vs. them, which seems ideological until you face the reality — if you don’t protect your body, your soul is on the menu.

A few years ago, I revived an old existential quest to try to get to the bottom of what a “soul” is. As completely base as this impulse is, it’s a fun one to try and onboard when you’re in your thirties, having endured Saturn returns, hormonal shifts, different personality calibrations, and endless sticks of burning sage and meditation mats. It’s a heady mystery, of course, thinking about what animates us, distinguishes us from a chair, a corpse, a well-endowed zombie that runs off base instincts. It seems the filmmakers were interested in this as well, since the second half of the movie delves into what happens when the question of your mortality is accelerated, and you are forced to grapple with it in seconds, rather than years. What is the softest landing for a body, when the soul has seen enough?

In 28 Years Later, Spike’s mother, Isla (Jodie Comer) is dying of brain cancer that has spread from her body to her brain, or her brain to her body — no matter the manner, she is doomed. Rather than continue to journey through the zombie wasteland that mainland Britain has become, she chooses a peaceful death, and minutes later, in an inversion of A Wonderful Life’s angel-topping-Christmas tree scene, Spike situates Isla’s squeaky-clean skull atop Ralph Fiennes’ bone art. To describe it renders it a bit silly, but so do many rituals involving death, because though it’s inevitable, our entire excursion is avoiding thinking of us in this way. That’s all we are, in the end. Flesh, bone, and a grey mass of muscle that leads us to believe otherwise.

I’ve been obsessed with reading about AI-induced psychosis — stories about people who become so influenced by tools like ChatGPT that they start to hallucinate or spiral into obsessive thought loops that lead them to believe they are in the Matrix or they are demons, angels, otherworldly beings. It’s easy to read these and believe this scenario is unlikely to ever happen to someone who is fully tied to logic the way that every person believes they are, but if I understand nothing else, I understand susceptibility and how easy it is to be confused. In the film, Isla tells iodine-orange Ralph Fiennes that she knows that she’s confused — and still, she can’t control how her brain tricks her, making her believe that her son is her father, that she’s in an unreal world.

There’s a sequence in the film that gives us a glimpse into how the island that Spike’s family has been living in has been doing so in quarantine. They seem to be living peacefully, if cautiously, and it’s a cottage-core dream — Spike is so sheltered from the evils of the modern world that he thinks Juvederm is a reaction caused by a shellfish allergy. The education system that the island has devised trains children to defend themselves against the Infected, using weapons of minor destruction like arrows and running. They’re taught how to be farmers, seamstresses, fishermen and “councillors” by Aaron Taylor Johnson’s sexy young mistress. It made me think of Ted Giola’s and Matthew Gasda’s excellent recent meditations on how to navigate the rise of LLMs and the education system. Giola suggests that all educators should adopt the Oxford method, tutoring students in smaller sessions, demanding that they recall information orally and reproduce arguments that are original, sans screen. Gasda has a less prescriptive take, instead arguing that because language is an intrinsic human right, students need to be motivated to see literacy as a way of marking themselves “alive.” Gasda writes:

“Soul as a notion is a rallying point; you can have a soul which goes to heaven, and you can also have a soul so that you’re not a cyborg. Soul—and the embedded concepts of internal coherence, purposiveness, uniqueness—provides incentive to work: a soul, like a muscle, can be built up and trained; a brain, conversely, is just a less efficient LLM. Students who feel like machines will use machines; students who feel like something more might have some reason to draw boundaries with technology.”

The ending of 28 Years Later is indubitably a setup for what feels like an insane and entertaining sequel, but for me, it doesn’t change the fact that this seems like the most substantive genre movie I’ve seen in a while — it’s not about survival so much as it is about choosing the preservation of soul. The cold opening of the film features a priest, who, instead of being afraid of his impending death at the hands of the Infected, is elated — the Reckoning is upon us, and it’s implied that he is at peace with the fate of his body because his belief system will preserve his soul. The film does not seem interested in disproving or interrogating the spirituality at play, only to posit that there is enough room for all our skulls in the bone forest. Thank you, Ralph.

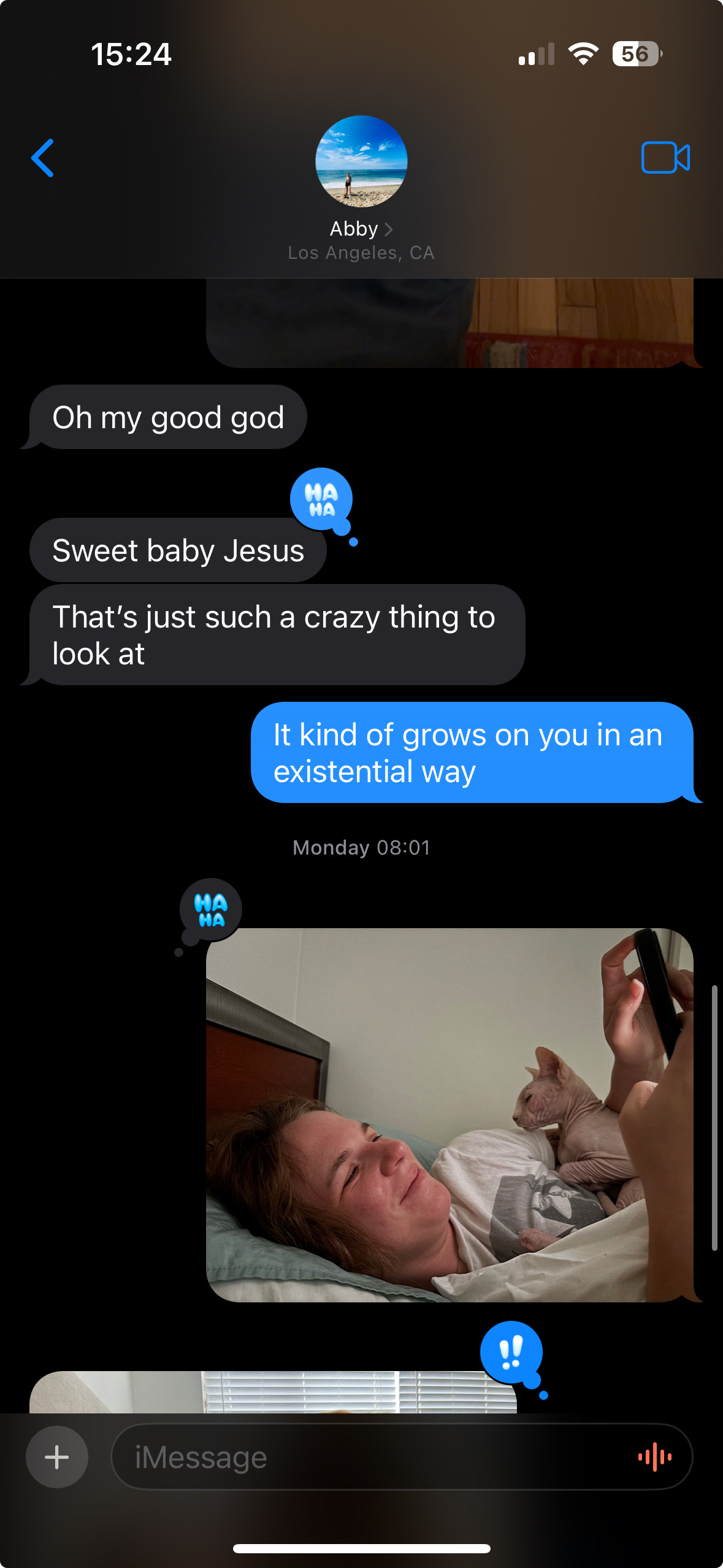

(The way I feel about the exposed spinal cord is the way I feel about this naked cat I’ve befriended — We Are All Like This Beneath The Fur, ya dig?)